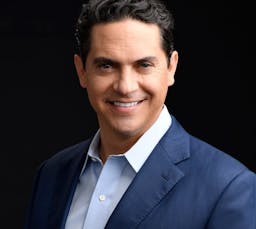

Monte Tynes

I was born and raised Ocean Springs, Mississippi. I went to the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, GA and earned a degree in Civil Engineering. After working for an engineering firm while in college, I knew I was not meant to be an engineer. I went back to Mississippi for law school. My Dad got me a job back in Ocean Springs with a great trial lawyer after my first year of law school. This is where I knew I would dedicate my life to helping people. While waiting on my bar results, Katrina destroyed the entire Mississippi Gulf Coast. I went to work as a DUI defense lawyer, and having all my court closes lost in the storm, I began trying DUI cases in jeans, a golf shirt, and a borrowed sports coat. After court one day, I stopped by my Dad’s makeshift office – his building was being gutted from the flooding of Katrina. After speaking for a while, my dad suggested I come work with him. So, working with him, I tried every type of case you can imagine, divorces, custody, construction, possession, DUI, domestic violence, and the occasional car wreck. Each day going to a different court room and trying a different case. Trial by fire. Then in 2010, I was appointed to represent a 14-year-old charged with capital murder. In July, my co-counsel and I tried the case for a week and the jury stayed out for 8 hours. Then found the young kid guilty, Almost all the jurors were crying when the verdict was read. The Mississippi Supreme Court reversed. In summer of 2015, we tried it again – this time in Oxford, MS in the courthouse in the middle of the town square – right out of a seen of a John Grisham book. This time with the guidance of David Ball, our now 20-year-old client was set free after spending 6 years in some of the worst prisons in Mississippi as a kid. After that, I was asked to represent a number of people against a corrupt local sheriff and got a verdict against him for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Most importantly, I’m the father of four amazing children and have a wonderful wife. My wife, while being a truly badass trial lawyer, is an amazing mother to our children. We spend most of our time traveling trying to spend time with our children, whether it be at a soccer tournament, cheer competition, football game, or spending the weekend tailgating in Oxford or Starkville with our college age kids.

Try your FRKN Case

Hosted by Lloyd Bell

Monte Tynes - Brown v. Keith, et al

$931,875.00 verdict on a $25,000.00 offer on a rear-end collisions case of less than 5 mph with no property damage to either vehicle.Police were not called to the scene and no medical treatment until the next day.Client had significant 10-year history of pre-existing low back injury.

Turning points:

- Opening Framing of the case – “Broke the law and caused a crash, looking for a free pass because the victim had been injured before.”

- No remorse from Defendant – 1st witness

- Demonstratives used to show injuries

- Independent witness to verify severity of injuries (program director of volunteer group)

- Defense’s cross of the Plaintiff shows medical bills include medical treatment for stuff that clearly was not caused by the crash, treatment for injury for 10 years up to the year before the injury, and medical records that showed she had the same complains before the crash as she had after the crash

- Closing – Being honest and admitting a mistake we made in the trial regarding medical bills

Bob Byrne - Our client was a 36-year-old college professor who was driving her SUV on a four-lane highway with her four kids. She slowed down with traffic. Behind her was a large, commercial dump truck that maintained speed and came upon the slowing traffic. The dump truck swerved and smashed into the side of our client’s car.

Our client was found to be alert and oriented at the scene. She went to the ER, complained of bumps and bruises, and was released that day. She and her family then checked into a local hotel where they stayed for four days. Our client could not bear to get back into a car to drive home, though home was only 30 minutes away.

We contended that our client had a mTBI and PTSD. Our client claimed that her life changed after the crash. She claimed that her teaching was impacted, and some student reviews supported that. But, four months after the crash, she was given tenure and promoted. Two years after that, however, she resigned from her position and took an assistant principal position with a small, private school for children.

At trial, the defense claimed that our client’s problems were due to her long-standing problems with anxiety. Our client had been given medication for anxiety before the crash but was not always compliant. The defense pointed out that she had marital problems before the crash, she had a demanding and stressful job, she was raising kids in a blended and interracial marriage, etc. They pointed to several times before the crash that she had been overwhelmed with life.

The highest defense offer before trial was $125,000. The jury awarded $1.75M plus pre-judgment interest of approximately $471,000, for a total verdict of $2.2M.

Here are the teaching points for the session:

- Make the trial not just a battle of credibility, but a battle of integrity. Expose the defense’s lack of integrity by showing that their claim to accept responsibility is not true, their witnesses cut corners, they ignored material evidence but focused on immaterial evidence, etc. We do a sort of polarizing the integrity of the case that we’ve found to be effective.

- As I learned from Jakob Norman at TLU Vegas a couple years ago, start the closing around the verdict form. It is the most important document in the whole case. “Verdict” means to speak the truth, but the form allows only a number to be written. Not an essay, not a speech. Just a number. That’s incredibly powerful and helpful.

- If your jurisdiction requires detailed expert reports (like in federal court), don’t take the defense expert’s deposition before trial (unless for housekeeping purposes or unless you want to blow the expert up to facilitate a settlement). If you do, the expert will see the weak points of their position and bolster those for trial. Perhaps more importantly, you want to make the expert uncomfortable and you want their body language to change when you do cross examination. The expert will feel far less comfortable if they are not accustomed to how you view the issues in the case, your rhythms, your cadence, your energy, etc. The jury may not get all of the nuances of the case, but they will see the expert squirm. You want the jury to see that discomfort and the inconsistency between the expert in direct and the expert in cross.

- Don’t value a case like how the defense does. The defense is all about diagnosis, ICD codes, CPT codes, and other quantifiable labels that fit into an algorithm. But the deliberation room is not equipped with computers, actuarial tables, artificial intelligence, etc. It is seven people sitting around a table valuing things based on their individual and collective experiences and values. We can’t make the mistake of falling into the defense’s way of doing things and focusing on the clinical aspects of the case as opposed to the stark ways the injury has impacted our client’s life. This is especially true with mild TBI claims, which can be very nuanced injuries.

- After exposing the battle of the case, ask the jurors for help. Unless a juror has a strong personal sense of justice that is implicated by the case, they will not necessarily feel invested to fight for a stranger. Fighting for a stranger is awkward in our society, where our default position is to be apathetic or to avoid conflict out of a sense of making peace. But asking jurors to fight empowers them – it gives them permission to have a stake in the fight and helps them see the importance of their work.

- Be willing to have “trojan horse” expert witnesses that you do not call at trial. In our last couple of trials we learned that the defense planned to launch withering attacks on two of our expert witnesses. In fact, we could tell that the defense planned to make those attacks the centerpiece of their defense based on the massive posterboards the defense brought into the courtroom. Both of our experts performed poorly in their depositions and if they performed poorly at trial it could have irreparably undermined our integrity and credibility. After concluding that we could get the experts’ anticipated evidence in through other ways, we elected at the last minute to drop both of those experts. The defense was flat-footed, and the jury was left with the lasting image of the defense having these massive posterboards at trial that they never used.

- If the defense expert only does a records review but does not actually examine the client, use the “negative space” technique to expose the weakness of their opinions. At this trial the defense expert did not examine the witness and testified in front of the jury that Lauren, my wife and co-counsel who was seated at counsel table, was the client. We set that up and actually had the jury laughing during closing..

George Moschopoulos & Andrew Ryan - White v. Rockport, et al. Verdict was $1.2M

Case description is as follows: Malissa White was employed as a nurse at nursing home where she was asked to participate in a Medicare fraud scheme. She reported the scheme to her employer and to the state, but her employer took no corrective action. Instead, her employer continued to require her to participate in the scheme. She refused and resigned. She filed suit claiming constructive discharge, or that she was illegally forced to quit. She found a job that paid her more than 25% of her prior salary within two weeks following her resignation. She made claims for non-economic damages only, but had not sought or received any medical treatment. Trial opened on Monday and a verdict was reached by Friday afternoon of that same week.

Here are our teaching points:

- The importance of focus groups and “losing” your case.

Cutting trial down to the bare essence. - Asking for non-economic damages when there is no treatment and the plaintiff earns more money at a new job.

- Understating your case in mini-opening.

- Making the ask in closing argument.

- Dealing with a difficult judge.

- Sealing the deal in rebuttal.

TLU Live HB Agenda

Track 1

Breakfast

7:30am - 9:00am

Hosted by

- 9:00a

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 10:15a

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 11:30a

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America

Sach Oliver · Joe Fried Winning the Most Common Tractor Trailer Case in America Lunch

Sponsored by

- 2:00p

Michael CowenGetting Big Justice in Big Rig Cases

Michael CowenGetting Big Justice in Big Rig Cases Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 3:15p

Joseph CamerlengoLecture

Joseph CamerlengoLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 4:30p

Randall Sorrels · Dirk Vandever Lecture

Randall Sorrels · Dirk Vandever Lecture

Track 2

Breakfast

7:30am - 9:00am

Hosted by

- 9:00a

Melissa Scartelli Charting the Path to Verdict: Strategic Decisions in Medical Negligence Trials

Melissa Scartelli Charting the Path to Verdict: Strategic Decisions in Medical Negligence Trials Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 10:15a

Rahul RavipudiLecture

Rahul RavipudiLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 11:30a

Brian PanishLecture

Brian PanishLecture Lunch

Sponsored by

- 2:00p

Ben B. Rubinowitz · Michael Kelly Lecture

Ben B. Rubinowitz · Michael Kelly Lecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 3:15p

Kimball JonesLecture

Kimball JonesLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 4:30p

Al Foeckler · Brett A. Eckstein Black Hat Justice Opening Statement

Al Foeckler · Brett A. Eckstein Black Hat Justice Opening Statement

Track 3

Breakfast

7:30am - 9:00am

Hosted by

- 9:00a

Kurt ZanerCreating Drama at Trial – how to tell a story in trial through dramatic theatrical techniques

Kurt ZanerCreating Drama at Trial – how to tell a story in trial through dramatic theatrical techniques Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 10:15a

John RomanoTactical Storytelling During Cross-Examination of Defense Damages & Causation Experts

John RomanoTactical Storytelling During Cross-Examination of Defense Damages & Causation Experts Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 11:30a

Sagi ShakedLecture

Sagi ShakedLecture Lunch

Sponsored by

- 2:00p

Kurt ZanerWriting a Story – Win your case in a page and a half

Kurt ZanerWriting a Story – Win your case in a page and a half Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 3:15p

Edward CiarimboliFrom the Windshield to the Boardroom: How FedEx’s Camera Systems Prove Control, Knowledge and Responsibility

Edward CiarimboliFrom the Windshield to the Boardroom: How FedEx’s Camera Systems Prove Control, Knowledge and Responsibility Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 4:30p

TLU ProfessorLecture

TLU ProfessorLecture

Track 4

Breakfast

7:30am - 9:00am

Hosted by

- 9:00a

Andrew PickettLecture

Andrew PickettLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 10:15a

Andrew Robb · Brittany Sanders Robb Maximizing Recoverable Damages Before Trial: Framing Your Case for Actual Recoverability

Andrew Robb · Brittany Sanders Robb Maximizing Recoverable Damages Before Trial: Framing Your Case for Actual Recoverability Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 11:30a

Dan AmbroseWitness Prep & Direct Examination

Dan AmbroseWitness Prep & Direct Examination Lunch

Sponsored by

- 2:00p

Patrick KangHow We Built An Eight-Figure Practice On Just Toxic Mold Litigation.

Patrick KangHow We Built An Eight-Figure Practice On Just Toxic Mold Litigation. Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 3:15p

Dan AmbroseCross Examination

Dan AmbroseCross Examination Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 4:30p

Eric CastelblancoSue Your Slumlord: The Ins and Outs of Habitability Law in CA

Eric CastelblancoSue Your Slumlord: The Ins and Outs of Habitability Law in CA

Track 5

Breakfast

7:30am - 9:00am

Hosted by

- 9:00a

Orlando De CastroverdeHow To Get A 1.7m Verdict On A Neck Injection Case

Orlando De CastroverdeHow To Get A 1.7m Verdict On A Neck Injection Case Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 10:15a

George MoschopoulosLecture

George MoschopoulosLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 11:30a

Al Foeckler · Brett A. Eckstein Black Hat Justice Verdict – A Deep-Dive into a $15 Million Verdict in an Extremely Conservative Venue

Al Foeckler · Brett A. Eckstein Black Hat Justice Verdict – A Deep-Dive into a $15 Million Verdict in an Extremely Conservative Venue Lunch

Sponsored by

- 2:00p

Michael StephensonLecture

Michael StephensonLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 3:15p

Alex IvanovLecture

Alex IvanovLecture Coffee & Snacks

Hosted by

- 4:30p

Sarah HavensLecture

Sarah HavensLecture